History

My grandparents emigrated from Russia to Africa to escape persecution. My father was an evolutionary biologist working in South Africa with Louis Leakey and Raymond Dart in the study of human origins. My mother was a ceramicist who introduced me to my medium as a young child.

In 1960 my parents moved to Australia to avoid Apartheid. In Sydney I was introduced to an oppressive colonial school system where I was punished and ostracized for my cultural differences. Moving to the United States in 1965 – a time of vast social change – I experienced liberation, and I began making pottery and sculpture in my mother’s studio. But in 1970, just as my new life began to feel real, my parents moved to Perth, West Australia.

I was angry. I attended two years of college philosophy and psychology at the University of West Australia, scraping by for a couple of years. Then I dropped out with the intention of becoming a farmer, but I supported myself by making pottery. Soon I moved to the Leschenault Peninsula near a town called Bunbury, a place so isolated that it was a six mile walk just to get to a public road. I didn’t own a car, a jacket, or even a pair of shoes. I built a house and a studio by the water, made of discarded lumber with a brick floor, without running water or electricity. I grew and caught my food. I began digging clay from a pit in the forest, throwing on a kick wheel, and wood firing pottery.

I spent five years in my studio beside the estuary modeling vessels on the wheel, seeking that perfect inflated shape that would stand as metaphor for a spirit I was trying to rebuild in myself. I needed to start at the beginning – a simple, pure, full form – like an egg.

In the forest I found a part of a life I wanted, but I still remembered my time in the U.S. as a time of freedom, so in 1979, at age 26 I moved to Los Angeles. I arrived with nothing. I lived in a garage at first, working as a laborer, but soon found work in a pottery factory, throwing mass-produced pieces.

As a profession wheel-throwing is very specialized. Once I’d mastered a production technique, I quit and went to another studio, and another. A year later, I was able to buy a wheel, build my own kiln, a rudimentary studio, and begin an exhibiting career once again.

Los Angeles

I arrived in L.A. with nothing.I lived in a garage at first, working labor jobs then found work in a pottery factory, throwing mass-produced pieces. Until then I had thought I was a good wheel-thrower,I went from one to studio to another to learn more techniques Finally, I built a kiln and began throwing production from a lean-to in my rented house. Finally, I was doing my own work again.

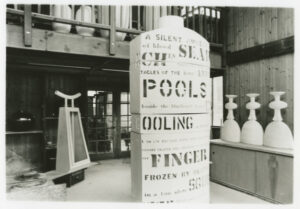

I applied the new techniques, but now made them in porcelain. I began developing 10th century Chinese type glazes. Soon I was commissioned to make hundreds of pieces for dozens of projects around the world. When you make a hundred pieces from one idea, none of the pieces is a perfect representation of the idea, but the entire body of work is the idea. I fabricated Plexiglas boxes, suspending vessels within. I began writing poetry and utilized the texts to link pieces into larger formats.

My studio was now divided. On one side I was doing work for design companies. I hired assistants, and also experts in model and mold-making, glazing and firing to build my repertoire of technique. On the other side I was developing fine art. I could afford to do experimental work. Over the next decade, with the fine art component growing in credibility, I freed myself from the design work and focused on making art.

As I developed the Multiples series, joining many pieces to form more complex systems, I began to see the connection with principles of evolution: how the identity of an individual becomes subsumed as it becomes part of a greater whole. From single-celled organisms to multicellular organisms, from complex organisms to individuals within groups, herds, flocks, schools, tribes…

As that interest emerged, I began to speak with my father about his life’s work in evolutionary biology. He brought up an antiquated biologists’ paradigm, “ontogeny recapitulates phylogeny,”

which means the development of the individual reiterates the developmental stages of the species. I saw this in my work and began reading avidly in the field.

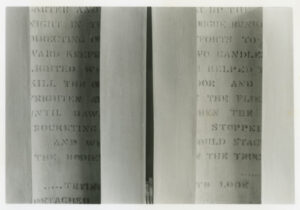

Creating a series of large rectangular vessels lined up, and a text came to mind I’d just read in one of my father’s lectures a description of early humans in which he wrote: “The environmental challenges to a naked, clawless biped with short jaws and small, low canine teeth must have been enormous.” It struck me as poignant and funny (and reminiscent of my own experience growing up with the man). I took this text and stenciled it across four pieces, rendering it in gold to reference illuminated manuscripts.

Over the next decade, my father’s work continued to inform my work. We talked regularly until eventually I wrote a book of short stories called The Boiling Frog, a series of fables based on evolutionary paradigms.

It’s not uncommon for an artist to work in series to explore an idea and get the totality of a picture through iterations. Even as a sculptor, I tend to work as a potter, perfecting a process in a long series as an exploration of an singular idea. This approach manifests through my entire career. I’ll make a hundred pieces to explore a single idea, but the moment I understand it thoroughly, the series is done.

My family left South Africa in 1960 because of Apartheid, the policy of systematic discrimination against people of color. For opposing the system, my cousin Raymond Suttner was arrested, tortured and imprisoned for ten years, ultimately on Robben Island along with Nelson Mandela.

In the late 1980s I walked into a store in Los Angeles to buy a pair of work boots. As I waited, I overheard the salesman talking to a customer about Rhodesia, which had recently become Zimbabwe, saying, “They don’t know how to rule themselves. They’ll just become another poverty-stricken African nation.” He was implying that indigenous Africans were somehow less capable of self-governing. This really pissed me off. I ended up in a shouting match in the shoe store, and went home to my studio frustrated. I hoisted a huge jar I’d just fired onto the garage roof and threw it off.

As it hit the ground, this object which had appeared to have so much mass dissolved into nothing. As I swept up the shards an idea came to me. I had some stencils around for packing labels. I used them to pierce a text I spontaneously wrote from two vessels. “All of the important possessions of my race and of my ancestors can be contained within these vessels.”

The piece pierced the illusion of mass, which was my metaphor for the illusion of wealth a racist country has when exploiting its population to the benefit of a few. Before, the vessel had a sense of density and mass. Suddenly it was more like a real body: an illusion of immortality that can be violated at any moment. I used the technique for hundreds of pieces extending the metaphoric.

I felt like I was finding my identity as a writer, and it was becoming an integrated part of my work. Around that time, my girlfriend Adriana told me her brother Eduardo needed a job. The family had lived in the infamous Aliso Housing Projects of East L.A. Eduardo had been a gangster and had a history of drug use, but when he’d discovered that his wife was pregnant, he got straight. He wanted a different life.

I taught him to make large forms. When he completed his first piece, as he signed it his eyes got really big. With a huge grin he said, “I’ve never written my name on anything that wasn’t a wall.” We became friends. He came in a few days later and said, “You, you can’t train me anymore.” I asked why, and he said, “I’m dying.” He told me he had AIDS. Those were the early days of the crisis when a diagnosis was an imminent death sentence.

At a big family gathering he told his eight brothers and sisters about his diagnosis. I met nieces and nephews, and ate far too much great food. We talked most of the night. Over the next months he worked for me as his health deteriorated. He told me stories about his life as a gangster on the streets of L.A. and in Mexico. The stories were colorful, horrific, gorgeous, nightmarish drama – all framed by his mortality. As he told them to me, I wrote the stories in a journal.

I asked his permission and used the texts for an enormous body of works. That exhibition in was one of the high points of my career. Eduardo was there with his little daughter. At the opening of the exhibition the parking lot was filled with Mercedes Benzes and lowriders. In the gallery

were two populations who would normally never speak to each other. The gangsters and the affluent art collectors were looking at each other, crying, understanding that they were affected by the same shared experience.

A few months after Eduard died, his wife relapsed, and we brought his daughter, Monique, to live with us. It scared me at first. Until then my writing had been about myself, but now there were these other people I had to focus on. At first I thought I was going to lose my direction, lose the inner voice that was informing my writing. But I couldn’t stop loving this tiny, abandoned girl, and soon I started hearing a new voice.

I’d come to know so much about Eduardo, Adriana, Monique and their family that I’d written stories they’d told me. I put them together in a book and generated a body of work. The exhibition ended up touring nine or ten museums following the first World AIDS Day in 1988.

During my stay in LA, I’d made a very close friend. Dusan Bogdonvic, a renowned guitarist/composer who arrived from Switzerland about the same time I arrived from Australia. We’d met in our first months there, and in the early days we’d played blues together in a club in Hollywood. We’d always wanted to do a project together.

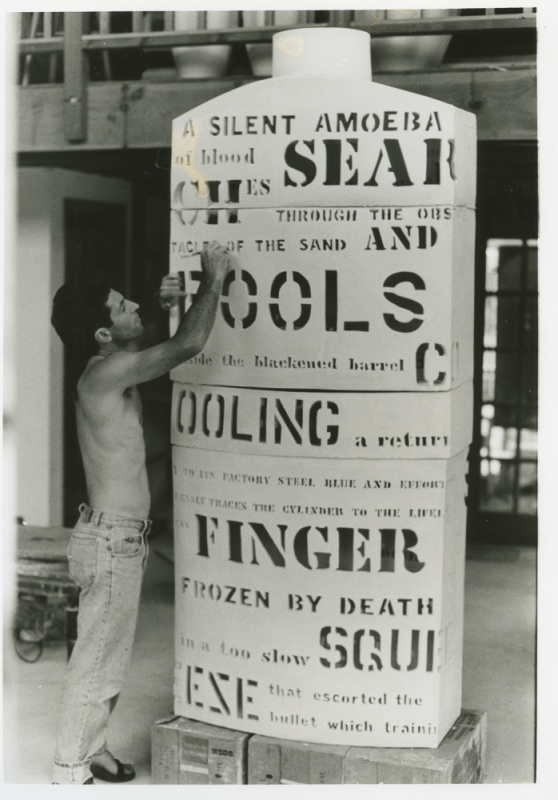

When he started composing music to a cycle of poems by Ted Hughes, called Crow, he invited me to collaborate. I made a group of huge works in clay (five to seven feet tall), with Hughes’ texts pierced through the surface. A French choreographer, Gilberte Meunier, who was working with the Pacific Dance Ensemble at the time, created a performance, jazz flutist James Newton, bassist Denise Briese, and singer Nmon Ford Livene performed the piece at the L.A. Theater Center.

Dusan’s Crow has subsequently been performed around the world.

Miroslav Tedic, a collaborator of Dusan’s invited me to play with the blues band he had formed together with a few of his fellow teachers at Cal Art, including composer/percussionist,. Art Jarvinen. Art’s percussion ensemble, The Antenna Repairmen, were in residence at the L.A. County Museum at the time. We collaborated on a number of pieces. He used a cycle of short stories I’d written called Little Deaths for a rhythmic recitation that was performed at Beyond Baroque in L.A. in the late 1980s. Following that we worked on a piece called Ghatam, named after an Indian ceramic percussion instrument played against the belly. I created 60 ceramic instruments ranging from porcelain bowls played with chopsticks, to

pounding tubes played with flip flop sandals, and African udu drums

Everything had changed. My career had taken its own shape separate from my intentions New people and experiences had reshaped who I was. I had become an unexpected father. In L.A. I’d found myself in my art. I’d found a career, friendship, and some peace of mind – things I’d never had before. A huge component of my life felt right, but another part felt wrong.

Being involved with the Los Angeles art scene was like riding some giant, undirected machine: If you had a place on that art machine, nothing could stop you. You could make and sell work, get a show anytime. I’d begun to have consistent museum exhibitions. But that art machine just rambles around randomly, directed by fashion and marketing. There’s an old saying that characterizes this: “The operation was a success but the patient died.” For me in the L.A. art scene, the operation was a success but the surgeon died. My career was picturesque and thriving, but I wasn’t interested in any of it anymore.

My new daughter, Monique, was three years old. I couldn’t imagine raising a family in L.A. I didn’t want to lose all my friends or the opportunities the city offered, but I wanted to take back part of what I’d left in the forest in Australia.

So I moved to Hawaii.

LEAVING LOS ANGELES

In 1991 my father sent me an academic paper on “Idealized Human Habitats.” The author showed images of tree canopies, elevations, proximities to water, densities of forest, to people from different places. Whether those people were Inuit from Alaska, or stockbrokers from New York, or New Guinea highlanders, there was a significant commonality in preference for specifics of an ideal environment. It all resembled the African savannah.

It seems that there’s an imprint within us for an ideal environment, one that’s rich in diversity, close to water, offering maximum potential for hunter-gatherers. Maybe when that interfaces with the creative part of us, we make gardens.

L.A. had been very kind to me. I found my identity in art, and built a career. But I felt estranged from the natural world, and my own essence as a person. When my new daughter Monique was three years old I moved to Hawaii. The east side of the Big Island is rainy and gloomy, perfect for gardening. I thought I could make the transition.

WORKING ON WAR SONGS

At the tail end of my time in Los Angeles I’d been writing a series of stories about my friend, Eduardo’s family, and their lives in and around the Aliso Housing Projects. One story I’d never completed was about his brother Victor who was a Vietnam veteran. The grief over his brother’s death had unleashed the buried pain of his war experiences for Victor.

He told me how his life had changed during his time in the Vietnam War, where he’d been ordered to fire on children. I wanted background for the story but he would say no more.

I was searching for someone to talk to me about what it was really like in Vietnam. Finally, I asked my L.A. art dealer, Grady Harp, who I’d known for many years, if he knew anyone who’d been there who might talk to me.

To my surprise he told me he’d been a surgeon in Vietnam. He said he’d send me some poems he’d written. Two weeks later, here in Hawaii, I found myself on my way back from the post office, reading his poignant works, tears pouring down my face…

Grady visited for a couple of weeks, and over the coming months I generated a huge body of work. War Songs toured a dozen museums across the country.

TRANSITION

The most immediate effect on my art of moving to Hawaii was a change in the relationship between my work and my writing. In L.A, my writing led the way for my sculpture. I’d published a few small books, and been asked to write movie scripts. My last major exhibition had been framed around the collection of short stories I’d written about the AIDS crisis.

I arrived in Hawaii with my four-year-old daughter, Monique who’d been diagnosed with AIDS at birth. To my astonishment she was rejected from pre-schools because she had HIV. I realized I could no longer use my work to speak openly. I needed to protect her privacy. I felt gagged.

My text-related work in clay ended. I wrote two books during my first years here, one compiling the children’s stories I’d written for Monique (which I didn’t release in Hawaii), the other a collection of fables based on my father’s work in evolutionary biology.

When I returned to clay, it was, for the first time in years, without text. I had to discover new techniques, new processes, and new glaze surfaces, all to reflect my new relationship with my work – one that didn’t involve words but could still speak. It took two years to develop.

When I was eight years old in Australia I would wander off into the bush. I would tie a rope to a tree and climb down cliffs, get lost in the scrub, cross rivers on fallen logs, stay there for whole days. I found peace and safety. There were poisonous spiders and snakes, but I found it much safer than being around people.

The information that nature offers is massive, complex, diverse, but it made sense to me even then. I never understood people well, the way they ostracize and hurt others… The garden is a place I feel safe and normal. The first thing I did when I arrived here in Hawaii, was to start gardening. I never stopped.

THE GARDEN

Sculpture takes its place in my garden the way iconography in a church finds its place – to create an experience. There is a certain height, a specific location, you pass it on your left or right, you get a certain feeling when you see it there, it becomes enshrouded by nature but not suffocated by nature.

When a piece gets broken by natural events like trees falling, the shards remain in place. I like seeing moss growing over them. Once in a while something really beautiful gets destroyed. Lightning struck a big tree in the front of the garden. One of my best black and white pieces below it was destroyed.

There was some sadness about that one. But I’ve come to embrace the process. There’s a dialectic between the amounts of work I make, what I lose in the garden, and what it costs me to live. I think it works out as a nice zero sum proposition at the end of it all.

The paths through the garden remind me of paths I followed into the forest as a kid. You descend into a valley. At the bottom of the valley there’s a river. You find a tree that’s fallen across the river and you climb across. You follow it down to a pool surrounded by mossy rocks, shaded by a cliff. You sit down and whisper to yourself, “This is what I will call home.”

SURFACES

The Song Dynasty Chinese potters made some of the earliest waterproof, vitreous ware. Glaze and clay became impervious. The aesthetics and function were integrated. There was a sense of permanence to the work, contrasting the earlier brittle, fragile earthenware. I was drawn to that integration.

Metaphorically, if the vessel is body, then the glaze is skin. Unglazed clay is vulnerable. For the In Vitro series, when I removed glaze from the fired clay, the Plexiglas boxes became glaze, skin. The glaze is also a window to look “through a glass, darkly” to memory, childhood…

The glazes I was drawn to most were not really about color. The Chinese celadons and ice blue Chuns had an opalescent or translucent water-like quality. The crackle patterns suggest that they are fragile, though hard. The copper reds read as blood.

Those glazes reflect my early belief in perfection, a Platonic ideal of form for all things. When I began altering my forms, pulling, tearing the clay, embracing accident, it was the beginning of a loss of belief in static form. Japanese glazes, particularly Shino, which crawls and shivers to reveal that which is below, then became more interesting.

The layering and combining of Japanese and Chinese glazes was a technical puzzle. It took years of experimentation to solve the chemistry concerns and firing problems. While the Song Chinese sought an idealized perfection, the Japanese Zen-influenced tea masters of the sixteenth century were interested in transience and accident.

As the tradition and techniques of Song stoneware traveled from China through Korea to Japan, clays and glazes changed. When work emerged from Japanese stoneware kilns of the Momoyama period, what might have been perceived as flaws in the ancestral Chinese type glazes, instead were embraced by the Japanese tea masters, generating an aesthetic that has remained vital for hundreds of years.

What attracted me to Song Dynasty glazes initially was that they invoked subtle characteristics of light absorption and reflection. On occasion I came to use metallic glazes to deny the medium. I have nothing against pottery, just sometimes it’s not the reference I want for a body of work.

The processes of making, altering, adhering, drying, glazing, and firing generate a sense of historicity for ceramic works – the feeling that events that led to its current existence happened in time.